By Jack Davis

Photo by me

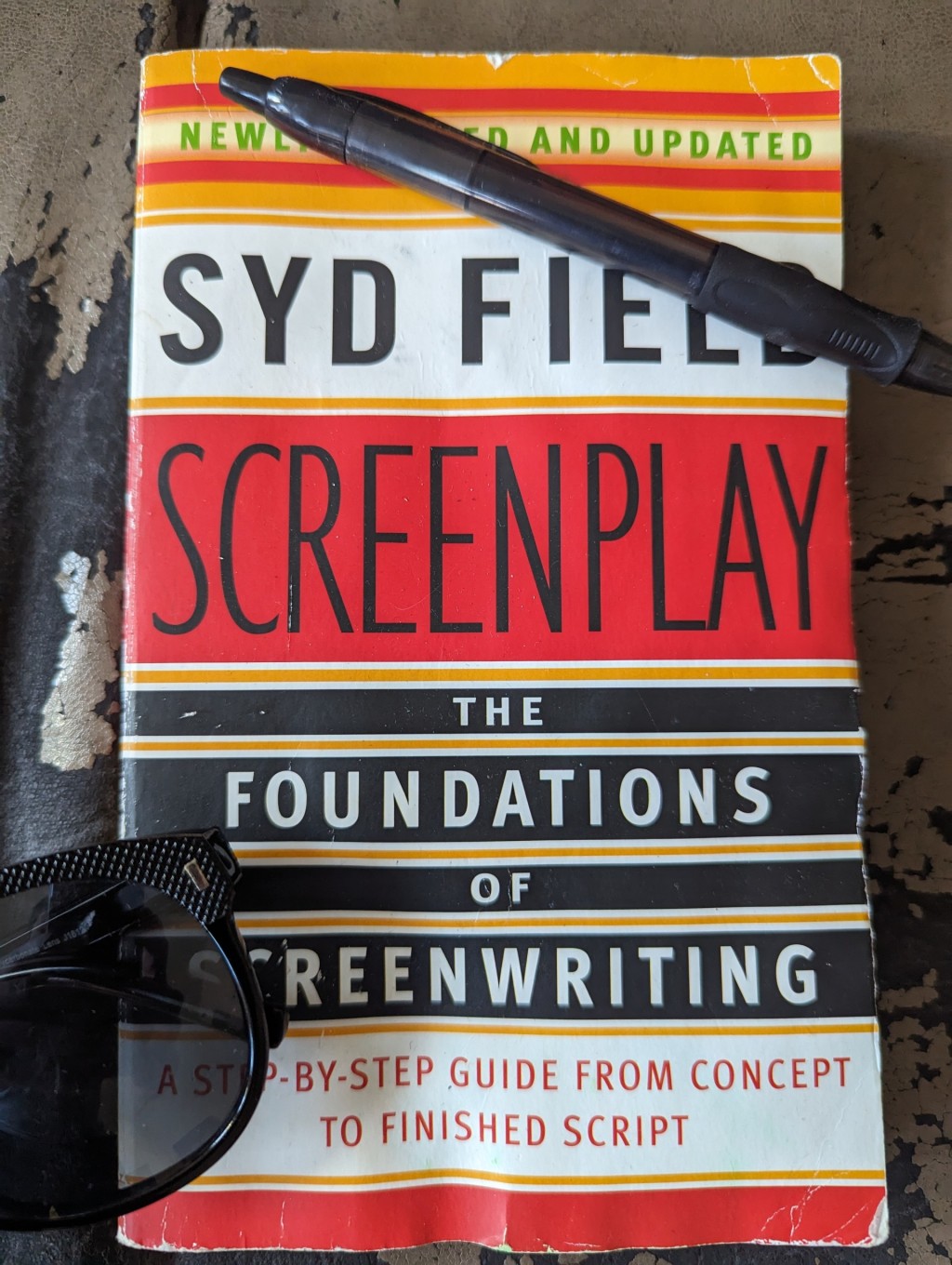

Hello, fellow readers and writers. Welcome to the final part of my three part blog series where I discuss elements from a chapter in Syd Field’s seminal book, “Screenwriting.” Last time, I got into the bulk of Field’s advice on script construction. This week I’ll continue with my thoughts, touching especially on openings. If you haven’t read the last part(s), be sure to before looking at this one as they’re all closely connected!

I gotta say, the first time I the quotes from Field – and even a bit now – I felt a little attacked. All the assumptions I made to justify – and tout – my writing style had been handily disproved in just a few sentences.

He’s right. The opening does need to be thought out, designed with visuals in mind, and you’re fighting an uphill battle if you don’t know how the beginning is related to the end. Reading this makes me feel like there have been moments where I’ve worked towards the ending trying to make sure that it relates to the beginning, when I should’ve been thinking about it in the complete opposite sense. I may have thought out my opening solely in the sense that I wanted it to be impactful; maybe the visuals were really good, the stage direction lines tight, the dialogue full of implications for the whole story. But I was in the same boat as the viewer, I didn’t know what was going to happen next, which isn’t a good sign for the strength of all scenes following. I was searching, not writing something calibrated to what I had found. There wasn’t any forethought, and this may seem to take away from some of the mysticism of that feeling you get when you’re writing, but I’m learning more and more that you need to have some minimal things determined – the ones he listed – before you let that writing beast out of the cage.

Photo by me

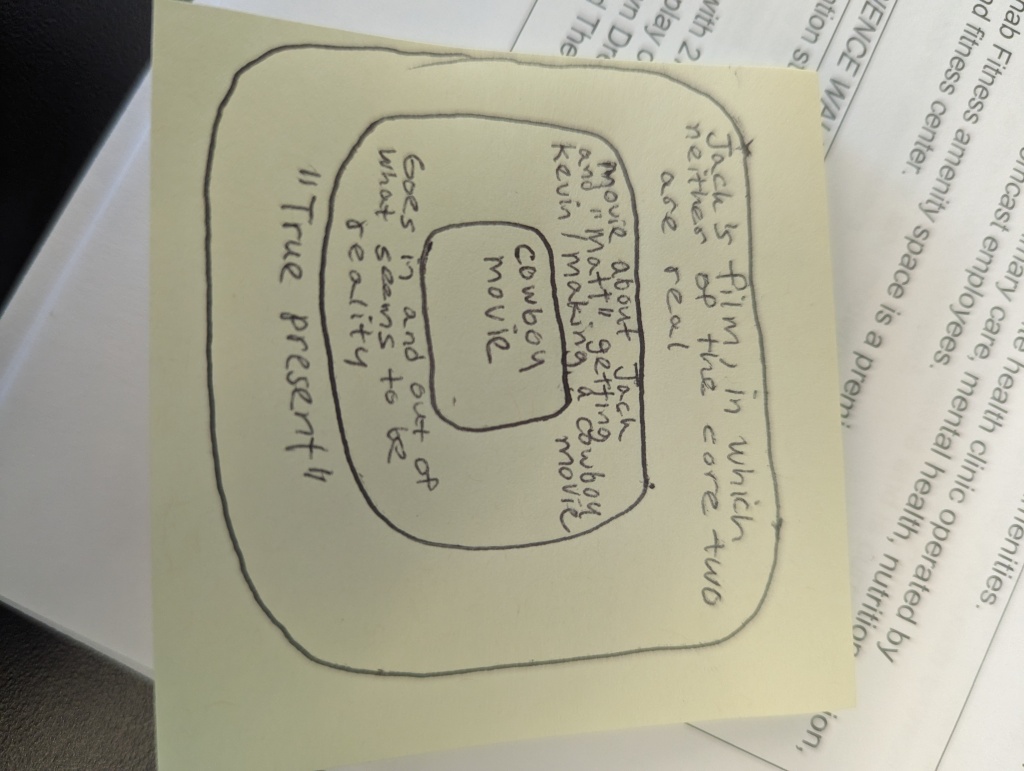

It’s essential to note – since he says you should know these things in the order he lists them – that he puts “ending” before “beginning.” I already discussed how I was going wrong about it, but doesn’t it make so much sense? The difference between how I was doing it and following Field’s direction is that with writing it this way, you won’t be in the same shroud the viewer will be following the first seen. If all things are done well, the bare minimum predetermined, then that shroud is a good thing for the viewer. But it’s not good for the writer

The same goes with plot point I and II. As long as it’s not a thought coming from sheer exasperation, it can be good if the viewer is somewhat jolted or in the dark after a plot point. It can be the sign of a very good movie, where you often think, “how the hell is the story gonna come back from this,” and then you’re amazed to see that the landing has indeed been stuck at the end. It’s not as difficult with the plot points; sometimes I’d think I had them in mind and I did, but they weren’t as sharp as they could’ve been, and they certainly didn’t create a distinct enough turning point in the progression. They were sort of just “there.” That’s why I agree these are also things that need to be figured out. It’s hard work determining these things, probably much harder than writing the actual script if you do it right, but I’m getting the sense that it takes a lot of time and frustration.

I want to emphasize that Field isn’t saying you have to know exactly what happens before the credits roll, that you must know that before you can write your screenplay. It just has to work effectively, and feel like a natural end to the progression. If you kill someone off because it “feels like a good ending,” it’s hard to justify that as evolving out of the arc of the film. You just need to know where all the sound and fury ends up, how it concludes. If the story is all about your character trying to get something back, does he? What does it mean for him if he doesn’t? Maybe him not getting it ends up being the right thing?

Like Field says, a little over or under 110 pages isn’t enough way to tell the story your way (at least not in the draft you end up showing people). I think the way he phrases it, though, can seem a little misleading and dooming. It’s not enough pages to tell your story the way you want it without knowing these things. It’s not enough pages to tell your story the way you want to tell it and have it work. It’s not enough pages to tell your story the way you want to tell it and have it be memorable.

On one hand, it means everything I thought about how I’d been writing may be wrong. On the other hand, it means that there are still so many ways I can get better, that maybe writing can be a little easier, that it might be possible to save some time without sacrificing quality. All that sounds pretty good to me.

Well, that was a wild ride. It was surreal and enlightening to read that chapter from Field again after not cracking that book open for years, even more so to write about it for all of you. I hope I provided some assistance / provoked some thought for some of you. Of those thoughts that – hopefully – come up, if there are any you’d like to share, I’ll be here.

Don’t be a stranger; I’d love for you to comment with any questions, concerns, or friendly disagreements. Also feel free to reach out to me through the “Contact Me” section of my page. Peace and love!

Leave a comment