By Jack Davis

Photo by me

To those of you tuning in for part two, hope all is well in your world. If you haven’t read part one, I’d highly suggest you go back before proceeding with this one; it serves as a sort of primer for where Syd Field comes from as a writer. Today I’ll be going into two – of the many – solid pieces of advice he gives on laying the groundwork for a successful screenplay.

Here are a two anecdotes / paragraphs from Field’s chapter “Endings and Beginnings” that made me rethink – for the better – my operating “style” of writing. The first time was in the beginning of the chapter when Field says:

“You’ve got approximately ten pages (about ten minutes) to establish three things to your reader or audience:

(1) who is your main character?

(2) what is the dramatic premise – that is, what’s your story about? And

(3) what is the dramatic situation – the circumstances surrounding your story?” Since he defines screenplay structure as “a linear progression of related incidents, episodes, and events leading to a dramatic resolution,” he says the answer to the question of how to best open your screenplay is… “KNOW YOUR ENDING!”

There’s a lot to unpack from all the Field says above. First, I want to note that any italics, bolding, or capitalization from up there was Field’s, and I thought it important to retain that form because it does a lot to get his message across. It sort of shows me that while it’s important to be feeling something during your writing process, to be inspired, to deliver something that has impact, none of that is negated by the need to do a little planning before you start. I think that’s where I got caught up. I had the notion that you couldn’t be one of the greats / have a wild story unless you flew by the seat of your pants, but after reading this I’ve come to the realization that this kind of planning is something a lot of the greats do, no matter to what degree. Seeing some movies it’s hard to believe that any of it could’ve been thought out beforehand, but I’d bet a lot of those writers had at least those above questions answered before they started writing. It’s not necessarily a crime if you write your first draft with absolutely none of this in mind and then come back to it, analyzing it through this lens; I’m sure a lot of great writers do that too, although it may not prove as freeing when you’re on a deadline (I hope to eventually have that problem). I just think it’s probably best to get into this practice sooner rather than later so you at least have it in your back pocket.

I don’t think it’s any accident that he highlighted “progression” and “related.” I’ve written things in one sitting or a few under the assumption that all of the events are related because I’m writing them so close together, as well as the assumption that I’m keeping some sort of log in my head to keep myself on track. A lot of getting into the weeds on a first draft, though, is writing the scenes that feel like they need to be written at that moment, because those are the ones that are most clear in your mind. That’s not a bad thing, the ones that stay may turn out to be some of / drafts of some of the best scenes, but that’s far from a guarantee that they go next to each other chronologically. They may be related events – I think part of what he’s getting at above is that every single scene should feel “related” – but next to each other in order, they may not strengthen a linear progression. Instead of zooming by, there’ll be this sort of dissonance for the reader analyzing it, and they might get held up on those two scenes; their reading process will be halted. The only time you’re really conscious of a “progression” – not the first word a viewer thinks of, which is a good thing – is when it’s interrupted, because otherwise your brain just thinks the movie “works” and leaves it at that. It’s not dissimilar to a heartbeat – I don’t know where all these biological analogies are coming from – if you’re noticing something about your heartbeat in the moment, I’d venture to say that doesn’t necessarily carry good implications. To my early protestations that my ending will be birthed from writing my story, Field says, “sorry, but it doesn’t work that way. At least not in screenwriting. You can do that maybe in a novel, or play, but not in a screenplay. Why? Because you have only 110 pages or so to tell your story. That’s not a lot of pages to be able to tell your story the way you want to tell it.” Well said.

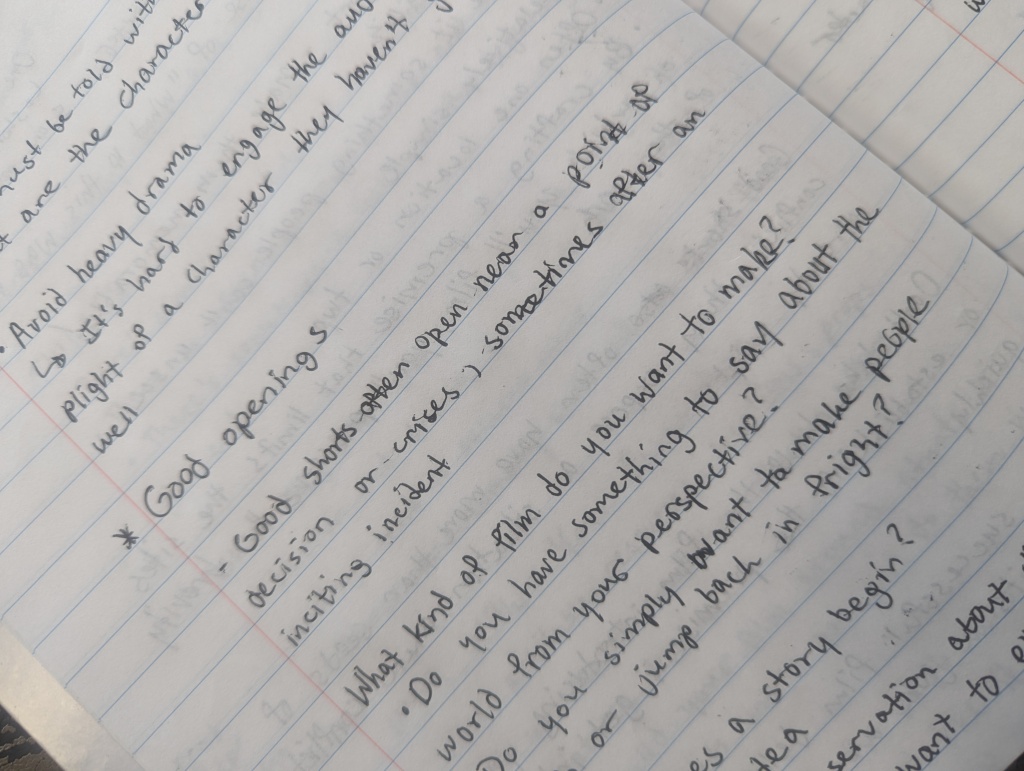

Photo by me

Another serving of wisdom comes in a short paragraph where Field further discusses openings and forethought:

“The opening of your screenplay has to be well thought out and visually designed to illustrate what your story is about. Many times I read screenplays and the writer has not really thought out his/her opening; there are scenes and sequences that don’t have anything to do with the story. It’s like the writer is searching, through and explanation, for his/her story.”

Directly after, he says, “before you write one shot, one word of dialogue on paper, you must know four things: your ending, your beginning, Plot Point I, and Plot Point II. In that order. These four elements, these four incidents, episodes, or events, are the cornerstones, the foundation, of your screenplay.”

I felt it might be useful to break up those paragraphs because even though it’s all shown as grouped together in the book, he’s touching on two different solid bits of advice, so I wanted to separate them at risk of them blending together.

I hope you’ve enjoyed part one and two of this blog series; I’ve certainly enjoyed writing it, and paging through this chapter again has helped me internalize a lot of stuff I forgot. That being said, no one practice for screenwriting or script planning is superior, so if you work a different way, or this post has helped you with your own process, I’d love to hear more.

Don’t be a stranger; I’d love for you to comment with any questions, concerns, or friendly disagreements. Also feel free to reach out to me through the “Contact Me” section of my page. Peace and love!

Leave a comment